NFAO Assertive Outreach book published in March 2011

Thursday, April 28, 2011 at 8:59PM

Thursday, April 28, 2011 at 8:59PM The National Forum for Assertive Outreach has published a textbook entitled ‘Assertive Outreach in Mental Healthcare: Current Perspectives’. I was engaged to contribute a chapter in collaboration with Sue Jugon, the Team Manager of the AO North based in Kettering, Northamptonshire. This presented me with a wonderful dual opportunity… to write a creative piece with enormous respect to the work Sue has done with her team over the last 11 years, but also to respond to the review in 2004 of my previous publication with Peter Ryan which referred to the work as ‘the funky business of mental health care’. I have long since wanted to expand on the theme of funky mental health, so here it is.

FUNKY MENTAL HEALTH

Steve Morgan & Sue Jugon

Warning: the following chapter should only be read by those with an open mind, and a challenging disposition!

Introduction

If you spend so many of your waking hours, and some anxious restless nights, devoted to working in mental health, are you right to expect at least some joy, fun, excitement, productive challenge, and even intrinsic reward from your complex interactions with service users and colleagues? Our managed, regulated, monitored and audited system is intended to ensure consistent good practice, but it is arguable whether it contributes anything towards producing a motivated workforce through its relentless pursuit of numbers and targets. A sea of fidelity scales, outcome measures, policy initiatives, service protocols and templates, research based models, and increasing mountains of paperwork may be a satisfying representation of service delivery for the academics and managers, but largely feels unconnected to the pursuit of genuine creative person-centred practice for practitioners, or service users for that matter.

The strengths approach to assertive outreach was fully articulated by Ryan and Morgan (2004), and in a review of their book (replicated in Practice Based Evidence, 2009) the approach was likened to ‘the Funky Business of mental health care’; providing practitioners with a different perspective from the mire of mechanistic, risk averse, box-ticking required by most organisations. The book places a strong emphasis on creative collaboration, true team-working and the need to be anchored by the well-being of the people we serve.

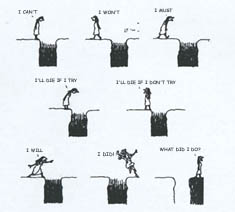

Continuing the theme of this book review, funky mental health should be seen primarily as working with and around the rules. It is about how different people may look at the same thing but see something different. A small proportion of all practitioners are exceptional in their ability to reflect on situations, think creatively about complex interactions, and manage the demands placed on them organisationally without losing their vision of person-centred practice as the most important goal. A small proportion of all practitioners are exceptionally poor, shouldn’t by rights be inflicted upon service users, but organisational systems and teams can be cursed by an inability to offload them. The large majority of practitioners are good people wanting to do good work, but become easily paralysed by their narrow interpretation of policies and outcome measures within the wider perceived context of a blame culture. They unintentionally prioritise a focus on what might go wrong before considering the challenges and often risk-taking demands of a genuine person-centred approach. The ultimate losers will always be the service users, though you wouldn’t necessarily believe this from the incredible spin the management machine can often place on its own contradictory demands of services.

Funky mental health is not about ignoring the rules or breaking the rules in any illegal way. Buckingham and Coffman (2005) talk about ‘First, break all the rules’, but only as a challenge to see and do things differently in order to gain the most positive and successful outcomes from identifying and working with anyone’s individual talents. Rules are generally guidelines, not usually immovable impositions or rigid barriers. Assertive outreach has been established specifically to find ways of working with people for whom the traditional rules of community mental health have proved less workable. So, by definition these rules, or norms, have failed to bring about anyone’s desired outcomes (neither service user nor service provider). In this instance do we give practitioners more time to do more of the same thing, in the hope of re-shaping the service user to better fit the pattern of service delivery? This undeniably represents a ‘service-centred’ approach to practice, and often includes punitive responses towards the service users and their needs. Or, do we give practitioners the permission to create new ways of engaging and working alongside the service users in creative and flexible ways (i.e. a more person-centred approach)?

Funky working needs a vision

In some instances funky mental health should produce the ‘I can’t believe you do that’ response from the majority of the good practitioners. It starts with a clear underpinning vision that can be returned to and checked against at any stage of a team’s development or experience of significant challenges. The vision should be about how we develop and sustain a ‘team’ that can incorporate the maximum range of qualities in a small group of practitioners so they may be made available to the diverse range of people who naturally make up the client group. It is about a clear underpinning philosophy, and an eagerness to reflect, individually and collectively, on the personal values that influence our every decision; including the big questions of why we do this type of work, what we feel about the people who need services, and how we intend to best work with them. It is about people who have a healthy respect for how work and personal lives inter-relate, not about rigid 9-5 demarcations. It is about genuine flexible responses to needs, rather than the rigidity of extended shift patterns. It is about being challenged to think, and being aware of the rewards of the intrinsic value of thinking through a challenge. In the world of funky mental health there is a more healthy developed appreciation of how much we become a part of service users lives; but also going one step further, seeing how service users become an important part of our lives if we have a belief in the value of the work we are doing.

Remaining contents:

What do the exceptional few do?

It is also about the environment

Underpinned by a ‘team’

Can local effectiveness be centrally legislated?

A Day in the Life

8.56a.m. … Morning Handover…

White Lightening…

9.49a.m. … Doing the work…

1.14p.m. … Team Reflection & Practice Development…

4.01p.m. … Administration Hour…

6.29p.m. … Real flexibility and response to needs…

7.00p.m. … A daily phone conversation…

7.11 p.m. … A call to the ‘buddy’

Conclusions

The practice of a funky mental health approach is not without its challenges and difficulties; not the least of which will be some staff members within any team who just don’t get it. There is no accounting for the lack of reflection and fixed mindsets that will regularly be encountered, and even denied or defended by those practicing them. For some, the opportunity to reflect on, think about, and creatively develop their practice is nothing more than a hindrance to just getting on with all the pressures they experience in a busy and demanding job. There is also no substitute for a good consistent moan to some people. This is not to say they do not do good work; but the amount of energy expended on negative feeling and expressions of emotion takes away from time that could be devoted to more constructive management of the challenges, but also serves to demotivate others subject to the whining and claims to have done it all before.

The individuals who practice funky mental health are a lucky few… predominantly reflective and ethical people, they understand how to achieve a level of enjoyment out of their work, it being an intrinsic part of their life interwoven with other elements of who they are. They encounter a majority of people who are eternally trying to find reasons to separate what they do at work from who they are as people outside of demarcated work hours. They understand that the less you integrate the more you fragment, and a fragmented life is the basis for further dissonance. However, these practitioners or team managers are not naïve enough to allow themselves to be exploited by the considerable demands of a system more equipped to grind down excellence for the sake of uniform bureaucratic mediocrity. They understand the system better than most, because they reflect on and analyse what is going on around them, and think about the sometimes hidden motives and connections in the games people play.

In the real world of person-centred practice funky mental health is about ‘permission’ to think and do things differently, rather than a ‘prescription’ of how things are expected to be done. Traditional expected ways can be fine, in some circumstances, but don’t have to be the usual way in all circumstances. Can funky mental health apply outside of AO? Yes, in the funky world of trying to recapture all that is interesting, motivating and exciting about working in mental health… assertive outreach could be seen as providing a guiding light for other areas of practice to adapt into their functions and responsibilities. Whether that will be understood from a higher level policy and management perspective is another question altogether.

To order the book click here.