Risk-making or Risk-taking?

Thursday, November 11, 2010 at 4:43PM

Thursday, November 11, 2010 at 4:43PM The following article was first published in Openmind (101, Jan/Feb 2000) and is reproduced with their kind permission.

Steve Morgan argues that assertive outreach is a positive service model that must resist being set up to be the new face of the 'risk business'

Assertive outreach (AO) is a term used to describe a range of services for 'people with severe mental illness who are hard to engage with services'. In 1998 the publication of Keys to Engagement by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health synthesized much of the existing knowledge and research on developing assertive outreach services in the UK, and there have since been a number of important developments in both theory and practice.

Assertive outreach (AO) is a term used to describe a range of services for 'people with severe mental illness who are hard to engage with services'. In 1998 the publication of Keys to Engagement by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health synthesized much of the existing knowledge and research on developing assertive outreach services in the UK, and there have since been a number of important developments in both theory and practice.

New service models have to establish themselves in the context of the prevailing political climate, and, undoubtedly, the current climate for UK mental health services is strongly influenced by the media portrayal of 'risk', despite what the evidence may say. Just as 'cost effectiveness' is inextricably linked to reduced hospital bed use, so new service models will be measured by their ability to achieve unrealistic expectations of 'risk elimination'.

Assertive outreach faces the danger of becoming closely associated with enforced restriction and compliance to medication regimes. Short sighted expectations imply that if hard to engage people are closely policed and made to take their medication, risks to the public will be reduced. Assertive outreach is potentially being set up to become the new face of the 'risk business', entrusted with the role of tracking resistant individuals, and equipped with the mechanisms of coercion and enforcement. Vote winner this may be, but a basis for effective services it is not.

In short, no consideration will be given to the reasons why people disengage, and service users' worst fears of 'aggressive' outreach will be fulfilled. The potential benefits of collaborative assertive outreach will be shattered, as more people feel driven to greater extremes of service avoidance. A good idea will be misappropriated, and turned into risk promoting failure.

Such 'policing' expectations of AO sit comfortably with traditional responses to potential risk, i.e. negative and restrictive practices. It also conveniently lets policymakers and some service providers off the hook, by avoiding the need to scrutinize their own gaps and failings. Far from offering incentives to engage, it confirms users' suspicions, and creates more distance between users and providers. In this scenario, 'risks' become more likely to happen!

I would like to propose the following definition of assertive outreach: 'A flexible and creative client centred approach to engaging service users in a practical delivery of a wide range of services to meet complex health and social needs and wants. A strategy that requires the service providers to take an active role, working with service users, to secure resources and choices in treatment, rehabilitation, psychosocial support, functional and practical help, and advocacy ....in equal priorities.'

An extremely small proportion of service users will resist mental health services at all costs, and some degree of restrictive power will need to be carefully considered on rare occasions. The majority of people labelled 'hard to engage' have been repeatedly demonstrated to engage when services are offered in a more flexible and client centred way. This has been equally true in UK statutory and voluntary sector agency AO teams. Most people will engage, at some level, with services they perceive to be in tune with their own needs and wishes.

The challenge to service providers is to be more flexible and creative in their active attempts to engage trusting relationships. AO approaches need to recognize the complexity of service users' lives, and the need to work with reasonable and practical priorities within the whole picture. It is not about reducing complicated social, cultural and environmental factors down to a narrow identification of symptoms, risk factors and strategies for restrictive management. The quashing of aspirations contributes to the potential for risk.

The established examples of good practice in AO recognize that risks are an integral component of comprehensive mental health services. They do not deny that people both pose risks, and are at risk, on a frequent basis.

The established examples of good practice in AO recognize that risks are an integral component of comprehensive mental health services. They do not deny that people both pose risks, and are at risk, on a frequent basis.

The AO definition given opposite offers a more holistic view of personal needs, wishes and aspirations. It encourages service users to express their own views of their world, to be listened to and worked with. This takes service providers into relatively uncharted territory, beyond the safety of 'professional judgement' and the more usual need to offer restriction as a solution to identified problems.

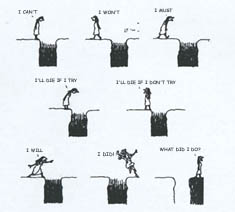

AO approaches therefore open up the prospect of 'positive risk taking'. The majority of the population enjoy the benefits of exercising choices and taking chances learning equally from the outcomes of success and failure. However, there is an implicit assumption that mental health problems should exclude people from such benefits.

'Positive risk taking' is not negligent ignorance of the potential risks. Nobody, especially service users, benefits from allowing risks to play their course through to disaster. Positive risk taking is about collaborative working, based on the establishment of trusting working relationships, whereby service users can learn from their experiences, based on taking chances just like anyone else. It is about understanding the consequences of different courses of action; making decisions based on a range of choices, and supported by adequate and accurate information. It is about knowing that support is instantly available if things begin to go wrong, as they occasionally do for us all. Positive risk taking is also about explicit setting of boundaries, to contain situations that are developing into potentially catastrophic circumstances for all involved.

The realistic emphasis is on 'risk minimization', not risk elimination. AO services expect to take responsibility and be accountable for their work. However, they need a more cohesive framework that clearly links responsibilities at individual, multidisciplinary team, and service organization levels. Responsibilities need to be strongly aligned to principles of good practice, clearly defensible in the face of the more usual damaging hunt for scapegoats. The culture that needs to blame dedicated individuals working in very challenging situations, is a culture that destroys the seeds of confidence and success before they have a chance to flourish.

Service providers and policymakers sometimes hear only the messages they want to hear, or read into the evidence that which they want to see. The result is that as a society we often get the services we deserve which are not necessarily the services that users deserve

Assertive outreach has a positive record of effectively linking the function of engagement to practical tasks and evidence based clinical interventions. Flexible and creative services hold benefits for both service users and providers who engage within them. They also offer a constructive approach to managing risks. Alternatively, we can hijack a good idea, to fulfil short sighted ideals.

Engagement by degrees

Assertive outreach workers recognize that engagement is not automatic; it has to be earned, and always worked at. It can frequently be tenuous, and in need of negotiation, but will always be the foundation of all other work.

- Someone reluctant to discuss mental health orientated issues may stil engage with discussions of their own priorities e.g. housing or money. Contact enables some trust to develop, and may form the basis for subsequent negotiations on more delicate issues.

- An individual feeling suicidal may feel their intense distress is being listened to and understood, if intensive support is offered at home through active listening. Hospital admission doesn't always guarantee safety, and may hasten an attempt for those people who feel they are simply having responsibility stripped away.

- Verbal aggression and agitation may occasionally be better supervised through non-judgemental support from respectful workers. Medicalizing the situation increases the volatility for some. Pranoid suspicions may be a response to reality, not psychotic symptoms. AO offers opportunities to observe and discuss social reality rather than psychiatric interpretations of individual behaviour.

- Someone who is chronically institutionalized and neglectful may be supported to remain in their own independent accommodation, through regular planned respite to enable cleaning of the home environment. Conversely, expectations of skill development and raised standards of hygiene may not always be realistic, and could lead to loss of tenure.

- A volatile and angry person, intent on the benefits of hard drugs, with no concern for the consequences of their aggression on others, will probably require prompt and restrictive interventions. But, only on the basis that efforts will be made to offer a wider range of supportive options when the situation settles

References

- 1. Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (1998). Keys to Engagement: Review of Care for People with Severe Mental Illness who are Hard to Engage with Services (SCMH).

- 2. PRiSM (1998) 'Psychosis study, papers 1-10' British Journal of Psychiatry 173, pp. 359-427.

- 3. Hemming, M., Morgan, S. and O'Halloran, P. (1999) 'Assertive outreach: implications for the development of the model in the United Kingdom' Journal for Mental Health 8(2), pp. 141-7.

- 4. Taylor, P. J. & Gunn, J. (1999) 'Homicides by people with mental illness: myth and reality' British Journal of Psychiatry 174, pp. 9-14.

- 5. Morgan, S. and Hemming, M. (1999) 'Risk management and Community Treatment Orders' Mental Health Care 31, p. 20.

Illustration: Jules Feiffer/1975 from Man Bites Man: Two Decades of Satiric Art (edited by Steven Holler, Hutchinson 1981).

OpenMind,

OpenMind,  assertive outreach,

assertive outreach,  risk in

risk in  Assertive Outreach

Assertive Outreach